Diagnosis and Treatment Guidelines

The Diagnosis and Treatment of Dravet Syndrome

The Dravet Syndrome Foundation funded an International Consensus Panel Study on the diagnosis and management of Dravet syndrome in 2021, thanks to educational grants from Biocodex, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and Zogenix, now a part of UCB. This built upon the previous North American Consensus Panel Study that was published in 2017. A panel of 20 clinicians with expertise in Dravet syndrome and nine parent caregivers answered a series of in-depth, iterative questionnaires about the diagnosis and management of Dravet syndrome. After reading a thorough literature review and drawing on their experience with patients, strong consensus was reached regarding clinical presentation, EEG and MRI findings, genetic testing, first and second-line treatments for seizures, and other aspects of treatment. The guidelines below were developed from the information in the North American Consensus Study (1), the International Consensus Study (2), and the 2022 ILEA Classification and Definition for Dravet syndrome (3).

Presentation of Dravet Syndrome

Dravet syndrome is an intractable developmental and epileptic encephalopathy that begins in infancy and proceeds with accumulating morbidity that significantly impacts individuals throughout their lifetime.

Initial presentation of Dravet syndrome includes:

- Typical seizure onset between 2-15 months, rare cases may present as early as 1 month or as late as 20 months

- Recurrent febrile or afebrile focal clonic (hemiclonic), focal to bilateral tonic-clonic, and/or generalized clonic seizures that are often prolonged

- Additional seizure types can emerge, usually between ages 1 to 5 years, including:

- Myoclonic seizures (50-90% of cases)

- Focal impaired awareness seizures (>50% of cases)

- Atypical absences

- Atonic seizures (<50% of cases)

- Nonconvulsive (obtundation) status epilepticus (10-49% of cases)

- Tonic and tonic-clonic seizures occurring primarily in sleep and in clusters

- Typical absences and epileptic spasms are atypical

- Hyperthermia, which may be associated with vaccination or illness, triggers seizures in the majority of patients; other triggers may include flashing lights, visual patterns, bathing, eating and overexertion

- Normal development and neurological examination at onset, with developmental slowing and delays evident from 12 to 60 months after seizure onset

- Normal MRI and nonspecific EEG findings at onset

Presentation in older children and adults:

In the absence of the early, characteristic history, the following features are characteristics of Dravet syndrome at any age:

- Persisting seizures, which include focal and/or generalized convulsive seizures, and, in many cases, myoclonic, focal, atypical absence and tonic seizures. Recurrent status epilepticus and obtundation status become less frequent with time, and may not be seen in adolescence and young adulthood

- Hyperthermia as a seizure trigger may become less problematic in adolescence and adulthood

- Seizure exacerbation with the use of sodium channel agents

- Intellectual disability which is typically evident by 18-60 months of age

- Abnormalities on neurological examination which are typically evident by age 3-4 years and may include crouched gait, hypotonia, incoordination, and impaired dexterity

- While EEG findings are generally normal at onset, background slowing and interictal discharges typically emerge by age 5 years

- MRI is typically normal, but may show mild generalized atrophy and/or hippocampal sclerosis as patients age

Genetic Testing

SCN1A mutations are found in over 85% of patients clinically diagnosed with Dravet syndrome. Mutations that cause Dravet syndrome generally occur de novo, but less commonly can be inherited. SCN1A mutations are also found in less severe epilepsy types, such as generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+), and more severe forms of epilepsy such as migrating focal seizures or SCN1A Gain-of-Function (GOF) DEEs; therefore careful clinical correlations are needed when interpreting SCN1A variants. Although information and research on GOF variants is still limited, SCN1A GOF DEEs may be suspected when seizure onset occurs before 3 months of age and patients present with a movement disorder. The determination between GEFS+ and Dravet syndrome can sometimes be difficult in very young patients based on either the clinical presentation and/or the genetic report. Recent research efforts developed a prediction tool to aid clinicians in determining the likelihood of diagnosis between GEFS+ and Dravet syndrome from the SCN1A variant and the age of seizure onset (Brunklaus et al 2022 doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000200028 Find the SCN1A Prediction Model here). Rarely, dominant pathogenic variants in other genes have been associated with Dravet syndrome, including GABRG2, GABRA1, and STXBP1, and rare recessive cases of SCN1B variants. The absence of an identified genetic variant should not preclude diagnosis of Dravet syndrome.

Experts strongly agree that genetic testing should be considered for all patients who meet any one of the following criteria, assuming the child’s early development is normal, there are no causal lesions, and the seizure etiology remains unknown:

- Single prolonged (5-29 min) hemiclonic seiure or focal/generalized status epilepticus (> 29 min) in the context of vaccination or fever in a child aged 2-15 months

- Single prolonged generalized tonic-clonic seizure in the context of vaccination or fever in a child aged 2-5 months

- Single prolonged generalized convulsive seizure in the context of vaccination in a child aged 6-15 months

- Single episode of afebrile convulsive status epilepticus in a child aged 2-15 months

- Single, prolonged afebrile hemiclonic seizure in a child aged 2-15 months

- Recurrent prolonged focal or generalized convulsive seizures with or without fever in a child aged 2-15 months

- Recurrent brief hemiclonic seizures without fever in a child aged 6-15 months

- Recurrent, hemiclonic seizures with or without fever in child aged 2-15 months

Genetic testing is recommended in patients of ALL ages, including in adults with a suspected diagnosis but for whom a detailed history of presentation in infancy may be limited. While simple SCN1A sequencing is appropriate when all clinical criteria are met, an epilepsy gene panel is the expert preference for children with suspected DS.

- Invitae’s Behind the Seizure Program provides no-charge genetic testing (epilepsy panel) for patients in the US under the age of 8 years that have experienced at least one unprovoked seizure.

- Another company, Probably Genetic offers no-cost genetic testing (whole exome sequencing) for pediatric-onset epilepsy.

More information about the SCN1A gene and other sodium channel related epilepsies can be found at the SCN Portal.

Early Diagnosis

Although there is no literature to support the benefits of early diagnosis, based on their clinical experience, the experts reached moderate consensus that earlier diagnosis improves long-term outcome for patients overall, with improved cognition and seizure control. A diagnosis also carries important implications for medication management, including avoidance of sodium channel blockers which have been shown to worsen outcomes in individuals with Dravet syndrome. Ultimately, an accurate diagnosis can be beneficial at any age, not only guiding treatment choices but also connecting families to networks of support.

Treatment

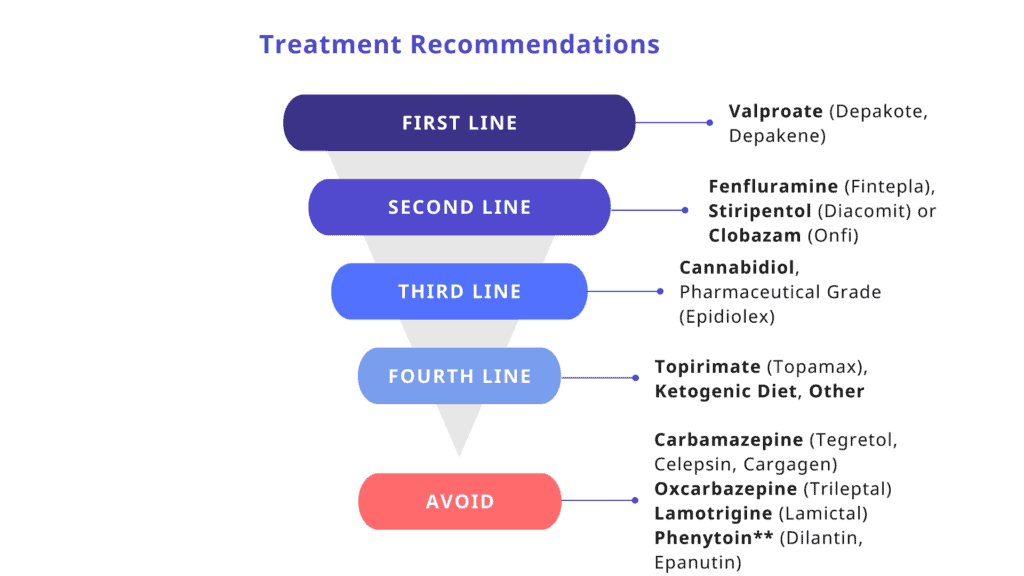

The treatment recommendations in the figure below were adapted from the International Consensus Panel Study (Wirrell et al 2022). The majority of patients will not reach complete seizure freedom; maximizing quality of life and limiting side effects of medications should be priorities when approaching seizure control.

“Other” includes vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), levetiracetam, zonisamide, bromides, clonazepam, and ethosuximide (for absences).

**Phenytoin may be of benefit for treatment of status epilepticus. Maintenance therapy with sodium channel blockers is contraindicated.

General Maintenance Therapy Recommendations:

- Consideration of dietary therapy (i.e. ketogenic diet, modified Atkins diet) is recommended following failure of 3-4 top line anti-seizure medications.

- VNS should be considered after the failure of top line treatments, including valproic acid, clobazam, stiripentol, ketogenic diet, fenfluramine, cannabidiol, and topiramate.

- Other surgical options to treat seizures are not recommended in Dravet syndrome. Experts agreed that corpus callosotomy has no therapeutic role in Dravet syndrome and temporal lobectomy should not be considered.

Treatment of Specific Seizure Types

- For focal or generalized convulsive seizures, physicians rated valproic acid, stiripentol, and fenfluramine as most effective.

- For absence seizures, physicians rated valproic acid and ethosuximide as most effective.

- For myoclonic seizures, physicians rated valproate as most effective.

Treatment of Status Epilepticus

- All patients with Dravet syndrome should have a home rescue medication (such as rectal/nasal diazepam or buccal/nasal midazolam) and a Seizure Action Plan that includes instructions for home rescue administration that has been developed with their neurologist.

- Intravenous valproate or levetiracetam should be next choices for prolonged convulsive seizures persisting despite the use of benzodiazepines.

- Intravenous phenytoin or fosphenytoin can be considered if the seizure persists following the above interventions.

Risk of Mortality and SUDEP

Patients with Dravet syndrome are at an increased risk of premature mortality, up to 20%. Patients may lose their lives due to accidents, status epilepticus, or illness, but half of the cases of premature mortality in Dravet syndrome are attributed to Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP). Experts strongly agree that patient families must be counseled about the significant risk of SUDEP at the time of diagnosis.

- Partners Against Mortality in Epilepsy (PAME) developed this Clinician Toolkit to aid in the SUDEP conversation with patients and families

- The DannyDid Foundation helps patients and families access seizure monitoring devices and other resources that may aid in the prevention of SUDEP and seizure-related deaths.

Wirrell, E.C., Laux, L., Donner, E., Jette, N., Knupp, K., Meskis, M.A., Miller, I., Sullivan, J., Welborn, M., Berg, A.T., 2017. Optimizing the Diagnosis and Management of Dravet Syndrome: Recommendations From a North American Consensus Panel. Pediatr Neurol 68, 18-34.e3. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.01.025

Wirrell, E.C., Hood, V., Knupp, K.G., Meskis, M.A., Nabbout, R., Scheffer, I.E., Wilmshurst, J., Sullivan, J., 2022. International consensus on diagnosis and management of Dravet syndrome. Epilepsia. doi: 10.1111/epi.17274

Zuberi, S.M., Wirrell, E., Yozawitz, E., Wilmshurst, J.M., Specchio, N., Riney, K., Pressler, R., Auvin, S., Samia, P., Hirsch, E., Galicchio, S., Triki, C., Snead, O.C., Wiebe, S., Cross, J.H., Tinuper, P., Scheffer, I.E., Perucca, E., Moshé, S.L., Nabbout, R., 2022. ILAE classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in neonates and infants: Position statement by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions. Epilepsia. doi: 10.1111/epi.17239

New ICD-10 Codes for Dravet Syndrome

Having the appropriate coding in a patient’s medical record may also make it easier to secure coverage for indicated medications and medical testing required for recognized co-morbidities of the disease. And, without a specific ICD-10 code, it is difficult to track how many people have the disease and where they are located. If patients are not being properly coded, we might not be accurately tracking all of the characteristics of the disease, as well as assuring that patients are receiving appropriate care.

The new codes are:

- G40.83 Dravet syndrome

Polymorphic epilepsy in infancy (PMEI)

Severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (SMEI) - G40.833 Dravet syndrome, intractable, with status epilepticus

- G40.834 Dravet syndrome, intractable, without status epilepticus

Treatment Information for Families

Seizure Medications and Treatments

Dravet syndrome is a spectrum disorder, meaning patients present with a wide range of severity and seizure types, and no two patients respond to treatment the same way. Still, several medications have been beneficial to many patients (sometimes called “first, second, and third line treatments”) and some medications can make seizures worse in patients (called “contraindicated” medications) due to their effects on the sodium ion channel. Below are the expert consensus recommendations on treatment of Dravet syndrome (also found in the section above as a figure). Even with top medication choices, most patients will not achieve complete seizure freedom; families work with doctors to maximize quality of life and reduce the amount of side effects while achieving the best seizure control. This balance can look different for every family.

1st Line: valproate (Depakene)

2nd Line: fenfluramine (Fintepla), stiripentol (Diacomit), clobazam (Onfi)

3rd Line: cannabidiol (pharmaceutical grade, Epidiolex)

4th Line: topirimate (Topamax), ketogenic diet/ modified Atkins diet, other (“other” includes: vagus nerve stimulation, levetiracetam, zonisamide, bromides, clonazepam, and ethosuximide)

AVOID: carbamazepine (Tegretol, Celepsin, Cargagen), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), lamotrigine (Lamictal), phenytoin** (Dilantin, Epanutin)

**can be considered for treatment of status epilepticus

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (or VNS) is listed under “other” as a fourth line treatment. While it can be effective, the benefits are limited, often resulting in less than 50% reduction in seizures. For this reason, experts recommend failure of the majority of first through fourth line treatment options before considering VNS.

Epilepsy surgeries beyond VNS are generally unsuccessful in Dravet syndrome. Experts agree that corpus callosotomy has no therapeutic role in Dravet syndrome and temporal lobectomy should not be considered.

Several patients utilize other treatment options, such as IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin) therapy, but there are not studies that examine the effectiveness of this treatment option.

Treating Seizure Emergencies

Many patients with Dravet syndrome experience prolonged seizures (status epilepticus) that require emergency intervention. Patients with Dravet syndrome should have an at-home rescue medication, typically a benzodiazepine, that is given during the seizure to stop it. Rescue medications can be administered in a variety of ways depending on the medication, including rectal, nasal, and buccal routes. Discuss options with your neurologist to find the medication and administration route that best meets the needs of the patient. Every patient with epilepsy should have a Seizure Action Plan that outlines how to respond in a seizure emergency. Visit seizureactionplans.org to learn more about developing a plan with your loved one’s neurologist.

Common rescue medications include:

- clonazepam (Klonopin)

- diazepam (Diastat, Valtoco)

- lorazepam (Ativan)

- midazolam (Versed, Nayzilam)

Seizure Triggers

Learn and avoid seizure triggers whenever possible. Common triggers for patients with Dravet syndrome include rapid changes in environmental and/or body temperature, illness, stress, over-excitement, patterns, and flickering lights. Fevers should always be treated aggressively with a plan established with the pediatrician and/or neurologist.

Day-to-Day Management

Children with Dravet syndrome typically need constant care and supervision, as well as help in avoiding seizure triggers (such as warm temperatures, abrupt temperature changes, overexertion, light/patterns, or excitement). Patients with Dravet syndrome may experience injury or even death from seizures, seizure-related accidents, status epilepticus, or serious illness. Patients with Dravet syndrome are at particularly high risk from Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP). SUDEP is not fully understood, but often occurs following a seizure while patients are asleep. Nighttime monitoring and seizure detection devices may reduce the risk of SUDEP. Equipment that has been found by families to be useful in the day-to-day management of Dravet syndrome includes video monitoring, protective helmets, cooling vests, pulse oximeters, seizure alarms, and glasses with colored lenses (for photosensitivity).

- DSF offers Patient Assistance Grants that can help with costs for equipment not covered by insurance.

- The DannyDid Foundation offers grants to assist with the cost of seizure-safety and monitoring devices.

Coping as a Family

A child’s chronic illness will have both direct and indirect effects on family members and their relationships. It is not uncommon for family members to feel denial, anger, fear, shock, confusion, self-blame, and helplessness. Family and grief counseling can help families deal with the complexities of chronic illness.

DSF provides access to online support groups for parents or primary caregivers that join our Family Network. DSF also has resources to support siblings of an individual with Dravet syndrome.