The Dravet Syndrome Foundation (DSF) held a Family & Professional Conference in Fort Worth, Texas on June 23-25 of 2022 in collaboration with Dr. Scott Perry and Cook Children’s Medical Center. DSF generally holds these conferences every 2 years, although due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there has not been an in-person conference since 2018. Needless to say, it was refreshing to come together in-person. I took on the role of Scientific Director with DSF in the summer of 2020, so this was my first time experiencing this event outside of the virtual environment. I was so impressed with the diversity of attendees- families navigating life with Dravet syndrome (including caregivers, patients, siblings, and extended family), researchers working to uncover the biological mysteries that still surround Dravet syndrome (DS), health care professionals across a host of specialties that treat patients with DS as well as contribute to clinical research efforts, and members of industry ranging from small biotechnology companies to well-established pharmaceutical companies. Emphasizing the success DSF has had in organizing these meetings and its leadership as an advocacy organization, we were also joined by representatives from another rare disease family organization that hoped to learn from the model DSF has established.

Here are a few of my biggest take-aways from the conference, with some supporting quotes from DSF Parent Ambassadors Rich Maxey and Shannon Cloud that give additional perspective from the conference weekend. Be sure to check out the conference webpage to view all of the recorded sessions from the conference.

Lots of new therapies are in the pipeline for Dravet syndrome.

The conference opened up with presentations from 7 different companies that have therapies in development or in clinical trials for patients with DS, and there were 17 exhibit tables representing companies and groups that develop or provide therapies or resources relevant to families with DS. Additionally, there were several talks focused on the early scientific work on development of new therapies including:

- a presentation by Dr. Gaia Colasante on experiments in mice that suggest genetic therapy may be beneficial even at older developmental ages in DS,

- an overview by Dr. Cameron Metcalf of the program funded by the NINDS to screen potential therapies using mouse models for epilepsy and work they have done in a mouse model specifically for DS,

- the preclinical work led by Dr. Lori Isom using a mouse model to investigate an antisense oligonucleotide approach for the treatment of the genetic cause of Dravet syndrome (which is now a therapy being testing in clinical trials by Stoke Therapeutics),

- an explanation by Dr. Andrew Escayg of the development of neuropeptides, and particularly oxytocin, as a treatment for epilepsy using a novel delivery method,

- and a session with Dr. Scott Baraban on how his lab has been utilizing zebrafish for large-scale discovery of drugs to treat epilepsy that have led to human clinical trials for Dravet syndrome.

For a disease caused primarily by a single gene, the genetics can still be complex.

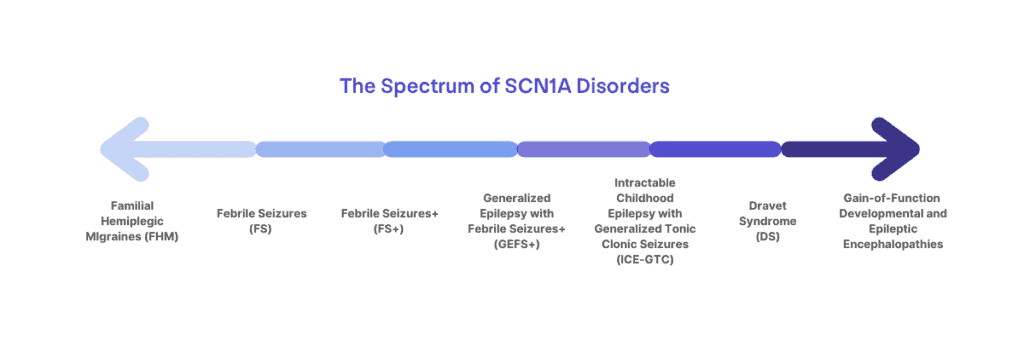

Dravet syndrome is considered a monogenic disease; meaning mutations in a single gene, SCN1A, cause the majority of cases of Dravet syndrome (with a few exceptions of patients with mutations in other genes or lacking a genetic diagnosis). However, disease-causing mutations in SCN1A are complicated. Not every mutation in SCN1A results in Dravet syndrome (see spectrum graphic below). There are actually a range of diagnoses that can result, depending on the mutation type and location along the gene, ranging from less severe epilepsies to Dravet syndrome along the more severe end of the spectrum. Understanding the genetic testing report and mutation type is important, as Dr. Ingo Helbig pointed out in his overview of genetics in DS. Because our knowledge of genetics is ever-increasing, revisiting previous genetic reports, or re-testing if a previous genetic test did not find any results, every several years may be worthwile. Dr. Helbig’s overview was exceptional, and in addition to highly recommending you watch the recorded session, I will also point you toward his own blog post about this topic. Sometimes, even with a clear understanding of the genetic report, it can still be difficult to determine a diagnosis based only on the mutation type. Dr. Andreas Brunklaus expanded further into a few examples of the complexity of SCN1A-genetics and diagnosis in his talk, such as the difficulty in distinguishing GEFS+ and Dravet syndrome in young children with certain SCN1A mutations. Dr. Brunklaus shared about a new prediction tool he helped to develop that can aid clinicians in diagnosis of SCN1A-related GEFS+ versus DS. Both Dr. Brunklaus and Dr. Helbig also discussed the topic of gain-of-function mutations in SCN1A. Mutations that cause Dravet syndrome are called loss-of-function, which just as it sounds, means the sodium channel made by SCN1A has reduced activity either because it works less efficiently or less of it is made. A gain-of-function mutation, however, results in the sodium channel having some additional activity that it should not. Gain-of-function mutations that are in certain areas of the gene can result in epilepsy syndromes that actually present with seizures often much earlier than in Dravet syndrome and sometimes with additional symptoms such as joint contractures and movement disorders. The distinction between these disorders and Dravet syndrome are important, because patients with gain-of-function SCN1A epilepsy disorders might actually benefit from the use of sodium channel blockers that are contraindicated in Dravet syndrome. While it still may be difficult to spot gain-of-function mutations in the genetic report with current knowledge, an indication to look more closely at the genetics would be seizure onset prior to 3 months of age.

Adults with DS are getting more focus.

Patients with DS and their caregivers are met with a whole new set of challenges as they reach adulthood. We were lucky to have several adult neurologists who presented at the conference. In one of the first talks of the day in the clinical session, Dr. Fabio Nascimento, an adult neurologist about to begin practicing at Washington University in St. Louis, gave an overview of the treatment of DS. Dr. Danielle Andrade, an expert in genetic epilepsies in adults, presented on DS in adulthood and some of the research she has led to better characterize the issues adults face. Dr. Seth Keller, an adult neurologist and advocate for better care for adults with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy, was also in attendance and gave a talk on caring for adults with DS. In the caregiver and family-focused sessions, an entire track was dedicated to the issues faced by adults and their caregivers, including an introduction to adult transition, some focus on adult siblings and their role in transition of care, and a workshop (Part 1 and Part 2) to help develop better resources to help with these long-term adult care challenges.

In addition to these sessions, DSF also had the opportunity to invite adult neurologists with an interest in learning more about Dravet syndrome to attend the main conference as well as a special breakout session focused specifically on how to better support families through the transition from pediatric to adult care.

More research is needed related to comorbidities, treatments, and SUDEP.

Several of the clinical sessions focused on comorbidities, including sleep, behavior, and cardiac issues. Dr. Linda Laux presented on the risk of Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (or SUDEP), and how that risk is higher in patients with DS. Her colleague, Dr. Melissa Baltuano, discussed their research efforts to better understand SUDEP risk in DS and how this work fits into the research landscape of broader efforts by groups like the North American SUDEP Registry. There was also a talk about the role of epilepsy surgery in DS. What grouped some of these talks together for me was how much there still is to learn about these topics in Dravet syndrome. For example, it is well recognized that sleep and behavior are some of the top most burdensome symptoms beyond seizures for families, but the spectrum of what these issues look like for each patient, the most successful treatment approaches, and how those specifics breakdown across the population are less understood. However, the broad range of expertise of those with an interest in Dravet syndrome present at just this conference alone gives me a lot of hope for the future of these lines of research.

Connection is powerful.

It was not just the science, medicine, and education that made this conference special- it was the connections. The way this conference brings together so many groups of people with a connection to Dravet syndrome is exceptional, but what is truly special is the ability for families to connect with other families who truly understand their journey.

Adding to the special feel of the conference was the attendance by whole families- siblings participated in the Sibling Camp (big thank you to Zogenix, now a part of UCB) and caregivers could take their loved ones with Dravet to the Activity Room (big thank you to Ciara’s Light Foundation).

I can say, as someone who has walked the paths of both caregiver and scientist, this meeting was impressive and powerful on both fronts. In the world of rare disease, it is even rarer to find this level of community, connection, support, research, and access to information. It was an honor to be involved in the planning and execution of the conference, but the supports for success of this conference have been laid painstakingly over the last 13 years by the hard work of DSF and families in the Dravet community. And of course, DSF is grateful for the support and immense efforts undertaken by researchers, health care providers, and companies bringing treatments to the clinic.